5 Lessons From Rory Sutherland

Rory Sutherland

The Vice Chairman of Ogilvy, a large advertising company, Rory Sutherland has a profound ability to communicate ideas about human psychology, marketing, and unconventional thinking in the most interesting ways.

I came to know of Rory Sutherland when he featured on Chris Williamson’s podcast – Modern Wisdom. The way he explains ideas and concepts around marketing and human psychology is nothing short of fascinating.

Since then, I’ve been hooked on listening to his speeches and podcast appearances.

This article shares 5 critical takeaways that Rory has taught me about human psychology and unconventional thinking.

#1: Explore vs exploit

Explore – To try out new things/experiment in hopes of finding new benefits.

Exploit – To make use of existing methods to generate benefits.

In any endeavor, we have the option to either explore uncharted areas or to exploit known ones. Unfortunately, people almost always opt to continue exploiting instead of exploring.

For instance, when it comes time for a company to come up with a marketing campaign or a new product design, they opt to simply exploit what has worked in the past instead of ever trying to find new, innovative advancements.

It isn’t surprising that us humans have a natural inclination towards exploiting instead of exploring. Exploring entails risk-taking, and the possibility of disappointment.

But in the words of Rory Sutherland: “You’ll never be pleasantly surprised” if you only ever exploit what you already know works.

When a company is planning out the launch of new products, if they only ever remodel and tweak their existing best-selling products instead of trying something new, they cannot expect the sales of this product to do any better than the old ones.

There is no room for growth. If you keep doing what you’ve been doing, you’ll keep getting what you’ve been getting.

That’s why we should reserve some scope for exploring. For experimenting. Because even though that entails risk, that is also the only place where true growth and massive advancements are made.

#2: The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea

For some reason, people have come to instinctively think that the opposite of a good idea is naturally and necessarily a bad idea.

But is that really the case?

Take Wendy’s for example. Conventional wisdom tells us that brands should present a clean, friendly image of themselves online to keep the brand image untarnished. This has historically worked well and is widely regarded as a good idea.

What would doing the opposite yield? What would presenting a rough, unfriendly image of your brand online do? Would it destroy brand reputation?

Wendy’s found out first hand.

Wendy’s Twitter account went on a rampage of “roast” style tweets, displaying a sarcastic, sassy and brash personality. This was the exact opposite of “conventional wisdom” in social media marketing at the time.

And it turned out to be an incredible success. Their tweets garnered millions of impressions. People were appallingly impressed by how raw and unfiltered their tweets were. The media couldn’t get enough of them.

By breaking the mold of what people associated brands behavior with, Wendy’s enjoyed massive success.

Goes to show that the opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.

#3: Engineering solutions vs behavioural solutions

This might be my personal favourite takeaway.

Rory often mentions that people have a huge bias towards solutions that involve hard science and infrastructure (engineering solutions) over solutions that involve manipulating human psychology (behavioural solutions).

Rory Sutherland argues that it is often far more economical to simply implement a behavioural solution than an engineering one.

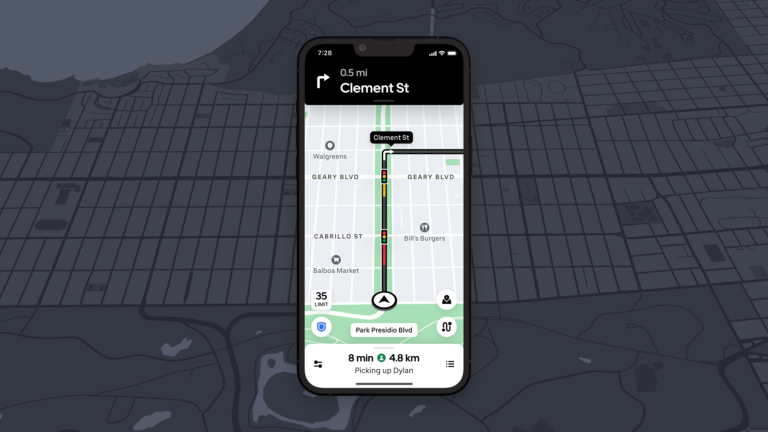

His case and point comes from the Uber Map. The problem that Uber faced was customer dissatisfaction because of long wait times.

If Uber were to pursue a “engineering solution” to this, it would likely involve sophisticated algorithms to get drivers to move to certain areas right before high-customer traffic periods. Not only would this be difficult for the development team, it would also be expensive.

Instead, they could just create a map that shows the location of the driver relative to the customer. This one change gave customers an array of benefits. Most notably:

- It removed any uncertainty about the location of the driver.

- It gave a sense of progress as they saw the drivers car get nearer.

With the addition of a simple map, customers didn’t perceive waiting to be nearly as much of a trouble as they used to. This essentially solved the problem at a much cheaper cost than pursuing an engineering solution would.

In another example, Rory Sutherland mentions that in a particularly tall building, people were complaining that the lift was too slow.

The obvious answer would be the engineering solution. Fork out of hundreds of thousands of dollars to upgrade the lift system and increase its speed.

But an equally effective behavioural solution was found. Instead of changing the elevators, they simply placed mirrors at the lift lobbies. People used the waiting time as an opportunity to check themselves out and touch up on their appearances. This subtle change completely reduced user dissatisfaction at the long wait times. Suddenly, the waits didn’t seem so long.

These examples show how changing peoples’ perception is just as powerful (and far more economical) than attempting to change reality. Which is why Rory Sutherland is such a proponent of behavioural solutions being taken just as seriously as engineering ones.

#4: Unteachable things

“The construction worker knows how to reverse a giant truck into an ally better than the engineering and physics professor at Yale.”

#5: Certain progress is immeasurable

Corporate culture is over-obsessed with KPIs and progress tracking. So much so that people forget or choose to ignore the reality of invisible progress.

This is particularly an issue in creative fields.

On this point, Rory Sutherland brings up the example of architects. Suppose that we have 2 groups of architects – the creative kind and the systematic kind.

If given a project to work on, the systematic architects might get to work immediately. Drawing up plans and drafts of designs.

On the other hand, the really creative group of architects might just be sitting around, thinking, staring at the wall, and searching for inspiration. On the surface, there seems to be no progress being made. One might even call these people lazy. Because we can’t quantify or measure progress in thoughts and ideas.

But in reality, these highly creative architects are the world-renowned, highly revered ones. The ones that design otherworldly-looking skyscrapers and seemingly impossible structures.

Therefore, the creative architects sitting around and staring at the wall have actually arguably made just as much progress as the systematic architects who immediately started drafting designs and plans.

But society has conditioned our brains to be all too quick to bow to logic and systems over creativity and vision. Creative people are labelled as unserious. Dreamers are labelled as deluded.

All this, despite the fact that we know all the major advancements come from creativity and wild thinking.

People love the phrase “thinking outside the box”, but disregard the people that actually embody it.

Creativity and logic are not mutually exclusive. However, most people have been conditioned to disregard the need for creativity. It’s an innate part of human brilliance and ingenuity that has been shunned. But if you are willing to embrace and embody it, you have a trait that the vast majority of people neglect. That’s rare. That’s an advantage.